“Bill’s Landing” at Mill Point on the west side of Lake Tyers at Toorloo Arm, some fifteen kilometres north-east of the seaside tourist township of Lakes Entrance, Victoria was a popular destination for day trippers wanting to visit the Aboriginal Mission Station at the entrance of the Nowa Nowa Arm. On the afternoon of 29 December 1921, a party of holiday makers staying at the 22 room Club Hotel built in 1885 by William Hunter at a cost of £1,250 (“the hotel could boast the finest hospitality even in its first days”) decided to make the most of the fine weather with an excursion to the mission. In fact Mrs (Mollie) Eileen Finlay née Moroney (c1880-1950) (Springvale Botanical Cemetery), wife of 48-year-old Alexander Kennedy Finlay (c1873-1921) would say “it was a glorious day and there was not a ruffle on the surface of the lake. We were the happiest party imaginable”. Joining the Finlay’s in the party of fifteen travelling from Lakes Entrance were their best friends Mr Darrell Dysart Mackintosh Ray (c1885-1921) and family visiting the Gippsland Lakes for the first time, John James McDowall Barke (Lakes Entrance Cemetery), a retired storekeeper from Lakes Entrance, and Mr Leslie Marchant (c1889-1979), auctioneer and returned serviceman (Captain, 24th Battalion AIF 1915-18). Also making the trip of nineteen guests on board the launch Tamar owned by Mr John Bills were two girls and two young men staying at Toorloo House, the guest house of Mrs Marion Mills.

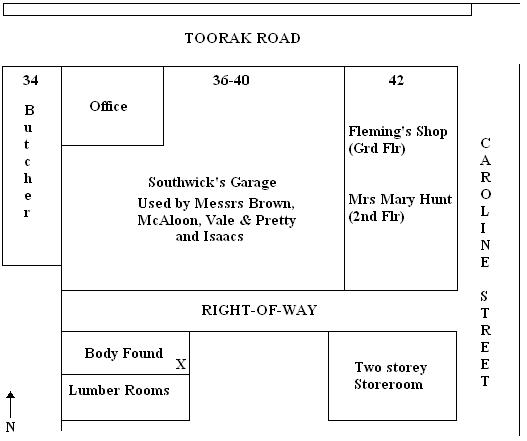

Soon after departing, passengers noticed something was wrong; the engine was making unusual noises and misfiring. One lady later claimed that benzine was leaking from the engine “and on looking down found that the volatile fluid was swilling about on the floor” leading Finlay to remonstrate with a passenger for smoking a cigar before demanding they return to shore; Harry Bills, son of the owner piloting the launch was alleged to have said “I can’t help it. I am only a visitor, and I am running the boat to give the owner a day off”. After reaching the middle of the lake, the situation took a turn for the worse and the engine suddenly stopped; Mrs Tassorette (Tass) Louie Ray née Setford and Eileen had a little fun with Bills saying “You don’t seem to know much about the engine, sonny”, who replied “As a matter of fact, I am only a visitor staying at the boarding house. I did work the boat last May, but I haven’t touched her since”. By now, oil was said to have been leaking but with the aid of Mr Bert Rhodes and Mr Elesmere McCausland, another returned soldier, managed to get the engine started. Ten minutes later, tragedy struck. It was 4:00pm and the launch was some 300 yards from the shore of the mission station. The engine suddenly stopped, backfired and a great pillar of flame shot up as high as the awning. Passengers quickly moved to the other side in safety during which Rhodes in an act of disregard to his personal safety gamely pulled down a number of lifebelts from beneath the awning and in the process getting badly burned.

It was a matter of time before the flames would ignite the oil and so the women and children started climbing out onto the side of the boat clinging to the awning while the men began a futile effort to control the flames. Nor did it help that there was no box of sand on the boat. Gently the boat tipped over and flung them into the lake. It was now a life and death struggle for survival. Eileen could not swim and found herself floundering in the water; her son (Alexander) John (1908-70, VX28486 Lieut Aust Army Ordnance Corps, 1940-45) was saved by a Miss Collins, nurse who noticed a floating life belt in the water. As for the other passengers, Tass Ray, wife of Darrell had a miraculous escape and didn’t even wet her hat. When the boat sank, she found herself standing head and shoulders above the water with the top of the awning beneath her feet. Bert Rhodes found one of the lifebelts and saved his wife and little daughter before helping others struggling. As for McCausland and Marchant, they “worked like heroes, not sparing themselves and taking terrible risks.” McCausland, described by Eileen as “game as a lion” swam towards a row boat some 100 yards away “saving at least 12 lives” while Merchant himself dived to the bottom and brought up Miss Marjorie Dashwood when she had sunk “never to rise again”. Not so lucky was Eileen’s husband Alex. He heroically rescued her as they both sunk to the bottom; on the third occasion, just after the rescue boat arrived she grasped onto an oar held out and his heart suddenly stopped. At that moment, Eileen noticed Darrell Ray, who had found his son Anthony ‘Chook’ Ray (b 24 Apr 1918, V90680 Sapper 64 Anti Aircraft Co, enlisted 21 Aug 1940) and swam him to the safety of his wife before returning to help the other non-swimmers. What happened next was a harrowing situation;

“While I was hanging to the oar, I saw Darrell sinking quite close. He looked towards me with a pitiful aspect on his face, and I stretched out my hand to him, straining every muscle to reach his fingers. I got within inches of him, but just failed to grasp him. He sank, never to rise again. It was a dreadful moment, for we had known Darrell since he was a bit of a boy, and Alex and I loved him”.

John Barke, like Finlay died not from drowning, but after suffering a heart attack; both bodies were recovered, but it took some time before that of Darrell Ray was found.

At the Aboriginal Mission Station, the Superintendent, Bruce Ferguson organised warm blankets for the survivors. The bodies of Ray and Finlay were both returned to Melbourne and accorded a funeral at the Brighton General Cemetery where they lie side by side (CofE*Y*1080-1082). Finlay was an architect of some merit (“Gibbs & Finlay”) who designed their home Kumalong – Kooyong Road, Caulfield while Ray, educated at Scotch College (1898) and a well-known Freemason cut short a promising career on the rise in the public service with the Taxation Department (1912-21); rising from officer in charge of correspondence to federal deputy commissioner of taxation. He was buried on the same day as Alma Tirtschke (q.v.).

Source:

The Argus 30 & 31 December 1921, 4 January 1922.

The Herald 30 & 31 December 1921.

The Age 31 December 1921.

Scotch Collegian May 1922.

Adams, J., “The Tambo Shire Centenary History” (1981).