(Ernest) Roy Busby (1917-85)

By Graeme Wheeler

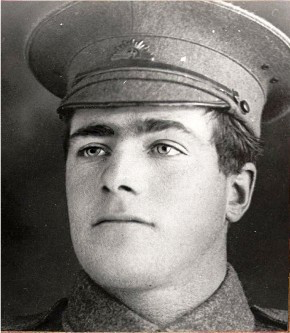

Ernest Roy Busby, known as “Roy” (Pres*M*20) was born in 1917, the only child of (Albert) Ernest Busby (1877-1945) and his wife May (1883-1964), shopkeepers, of South Yarra. From what is known, Roy’s childhood was a very happy one. He grew into a studious young man, commencing his tertiary education at University High School. Training as a biochemist, he obtained his first Diploma at RMIT before being employed at Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL), where he spent the next forty years until his retirement in 1975. In his early days at CSL, his field of expertise was the production of cultures to counter diphtheria and typhoid, and he later worked in the development of penicillin. As he matured, Roy’s recreational interests gelled into four main areas; bushwalking, mapping, cycling and statistics, and collecting books. But there was much more to his life than that.

Bushwalking

Roy became interested in geography and the outdoors at an early age, and by the 1940s, he had started a walking club among his fellow workers at CSL, some of whom followed him when he joined the Youth Hostels Association (YHA). He enlisted in YHA as Life Member number 18, and it was not long before he was recognised as an outstanding bushman, a quietly competent navigator and a most companionable track mate. Devoting all his recreation time to the exploration of Victoria, with a few like-minded individuals he walked in all the then wild places, carrying his pack for up to two weeks on extended trips in remote places. Almost every weekend was spent in this manner for perhaps a decade, from the nearer Dandenong Ranges, the Grampians, Wilson’s Promontory, to coastal and alpine areas. Later, as his interest spread interstate, he climbed Mount Chambers and walked its gorge in the Flinders Ranges, and Ayers Rock, Mount Conner and Mount Olga in the Centre, in the ‘Corner Country’ and the Kimberley. Roy had no ambition whatever to travel overseas; believing that Australia had all he wanted, and never changed that view. More often than not, walking gave him the opportunity to achieve a greater intimacy with the land, providing an interesting, if demanding means of satisfying his curiosity about landforms, botany, geology and natural history. One hundred and sixty-six mountains had been listed in the State; he was one of very few individuals who climbed them all. Similarly, there were one hundred and eighty-six waterfalls; he sought them out and described them. In answering his compulsion to record, he had taken up photography, compiling a collection of hundreds of slides from his trips. Roy was one of rare breed who denied ‘that speed was more potent than the view, and that hills were simply there to slow you’. In the 1950s, he joined the Melbourne Amateur Walking and Touring Club (later the Melbourne Walking Club), the second oldest walking group in Australia. Formed in October 1894, it initially was for male speed walkers – the harriers, but with the ‘discovery’ of bush tracks and trails, it was not long before the competitive aspect was abandoned and bushwalking as we know it was embraced. It was into this traditionally regulated, all-male club that Roy found companions there closer to his own age and capable of providing the intellectual stimulus he sought. One such man was Noel Semple, a fellow biochemist at CSL, and of equal importance, a walker who matched him in performance and interest in conserving the environment. It was not long before The Melbourne Walker, the Club magazine, published articles Roy wrote about his work on track measuring, mapping on Mount Buffalo and the Cathedral Range, pinpointing the location of Mount Thackeray in the Grampians, and the listing of Victoria’s waterfalls. For ten years before Noel moved to Canberra and married, he and Roy shared their annual leave at Mount Buffalo where they spent every day on long walks, increasing their daily mileages more and more each year. In the 1960s, Roy participated in numerous annual motor safaris into the Centre. Bill Kennewell, who established the concept, transported special interest groups to certain points in the ranges, off-loading walkers who wished to carry their packs across country to a pre-arranged rendezvous where they would be picked up some days later. At another time, Kennewell arranged a rare opportunity for his clients to explore the vast underground caves and lake systems beneath the Nullabor Plain, rigging up ladders to give access, providing inflatable boats for use on the water, and an improvised arrangement that provided plenty of light down in the huge caverns. Swimming underground in that primal place was absolutely unique. Roy brought back great photographic records of those adventures. “Buzza” was never deterred by difficult terrain. Being city-bred, one may be surprised that he had developed into such a ‘hard’ man, for he could handle anything the outdoors served up. Bad weather, rain, fog, steepness of the climb, lack of water, snow, cold, heat; Roy was always there at the end, invariably with a Puckish grin. His tolerance of pain and setbacks was abnormally high and his sense of humour inexhaustible. He could walk fast when required – he had to when in Noel’s company – and had a gamut of interesting personal foibles out on the track that included his greeting of a growled “Ho!”, his breakfast menu of Granbits, Farex, and a heavy but moist fruit concoction that he baked at least weekly. He called it “Ballast cake” and claimed it “stuck to him all day”. His favourite sweet, carried with his scroggin, was Cherry Ripe. Always eager to make the most of his time in the bush, he never ‘slept in’ when on the track, and those walking with him usually, but not universally, appreciated his drawled wake-up call of ‘Six o’clarck’. He became a legend among his contemporaries. There were fewer places he liked more than Tasmania, and from his first visit to the Cradle Mount-Lake St Clair National Park in 1952 Roy was determined to return. He was devastated at the flooding of Lake Pedder, but counted himself lucky he had experienced such a gem of nature before its insane destruction.

Mapping

From the age of ten, Roy was consumed by maps, even making his own as a child holidaying with his parents at Hepburn Springs, or of forest tracks in the Dandenongs when on picnics. It was a part of his intellectual make-up that demanded his recording of physical details of his environment, and persisted as an interest all his life. He began collecting maps and became familiar with the various types, finding where to obtain them, familiarising himself with their strengths and shortcomings. It was a subject upon which he became very knowledgeable. In the days before Australia was adequately mapped, many individuals sketched their own of favourite areas and shared them among walking friends. As there was nothing suitable on the Cathedral Range, near Buxton, Roy began a survey of that area, producing a first-class guide to all the tracks, peaks, cliffs and sources of water. Visiting the short range over many months, sometimes alone, more often with mates, with an accurate compass, altimeter and clinometer, his final draft was a most useful document for walkers. The trips done on his annual holidays on Mount Buffalo contributed to his new chart of the plateau, for the official tourist map was an imaginative depiction of a table-like structure with fluted walls dropping sheerly on all sides, the features on the top marked as little pimply excrescences. Not satisfied with the distances shown, Roy, the scientist, continued his own measuring technique, wheeling his bicycle over every metre of the network then averaging the two cyclometer readings. In his ongoing desire to climb all the mountains in the State, Roy came upon Mount Thackeray in the Victoria Range, the most rugged section of the Grampians. It was marked on maps but being located in the middle of a remote archipelago of outcrops and ravines on a high range, could only be discerned from afar. Many walkers had attempted to climb the mountain but it was a very elusive peak, and locating it proved to be the greatest obstacle to success. In 1955, in company with his mates, Roy made his first foray into the area. Having disposed of the initial climb of more than 1,200 feet up a cliff wall, it was discovered that the map was incorrect; Mount Thackeray was away off to the south. When a new geological map was produced in 1961, it was hoped the task would be easier, but when Roy and his company zeroed in on the mountain’s co-ordinates, to their chagrin, they found it was still at least two kilometres to the south. After eight sorties over as many years, Roy finally nailed its correct position, climbed it and made an accurate map. Those who participated in all those trips led by Roy had a definite sense of achievement that their persistence had paid off, and that he had filled in another small but significant part of the jigsaw. In 1953, Roy was asked to produce an index of maps for the Federation of Victorian Bushwalking Clubs. An inordinate amount of work was involved in collating all the information from and about maps useful to walkers, and nine years were to pass before it was published. It sold out within weeks. Roy had started collecting maps at an early age and his final tally included full sets of Australian 1:100,000 survey maps, historic, mining and tourist maps, hundreds in all. The introduction to the second issue of his Map Index sheds some light on his own progressive attitude to walking when he wrote this appeal for a more aesthetic appreciation of the environment – “Maps are often used for purposes other than navigation. For many bushwalkers, the final aim is not merely to see the view, reach the peak or traverse the stretch of country. These are the means, but the real end is to gain a sense of intimacy with the whole, and each individual experience is made richer if its significance in that wider relationship is not missed. To visit Moliagul, aware of its association with Flynn of the Inland and with ‘Welcome Stranger’ gold nugget is to illustrate this gain”.

Cycling

Although this activity began as a relatively low-key, normal, youthful pursuit, it ultimately took over Roy’s every waking moment as it grew into an obsession. When he began cycling in 1936 at the age of eighteen, he started keeping a methodical record of every ride he did, of every mile, and kept doing it throughout his life. Initially his purpose was to use the bike just to get out into the country, his first rides being to the east, to the nearby Dandenongs, and then to the outlying lands to the north and west around Melbourne. An ambition grew to do more than that; to see if he could claim some sort of record for distance cycled, and he began a daily routine of riding that was only broken by bushwalks with his mates, illness or accidents, of which there were a few. By 1945 he had settled upon a scheme delineating the maximum distance he could cover out and back in a day. He called this “boundary riding”; it was essentially an area within a radius of a hundred miles (160 kilometres) of his home and he treated the project quite seriously, planning the daily routes according to wind direction, weather, his fitness at the time and other variables. Although the objective was primarily to notch up miles, Roy made it as interesting for himself as possible. His weekdays began at five; he rode a few miles before breakfast, then rode across Melbourne to work. Another ride at lunchtime; the homeward trip and an additional burst after tea soon saw his tally rising. Writing up the log was done before he went to bed at eleven. The statistics that came out of this routine were quite staggering and encouraged him to raise his sights, not on an Australian record, but a world one, at that time held by a Scot, Tommy Chambers. In 1977, Chambers had pedalled nearly 800,000 miles. (1,287,440 kilometres), but at seventy-six, after a bad accident, was virtually finished. Roy’s best day’s ride of 307 miles (494 kilometres) was in 1951. Later he rode 511 centuries, of which 38 exceeded 200 miles (321 kilometres), 17 successive centuries including 11 on working days. He did 500,000 miles (804,650 kilometres) in 500 months and 20,000 miles (32,186 kilometres) each year for 10 years. He also rode 100 miles (160 kilometres) a day for 500 days, with 461 in succession. The high point of these achievements in the saddle, made between 1935 and 1984, was in the 1970s. Roy had lived happily with his parents and lovingly cared for his mother, who, around 1963, fell victim to dementia. Determined to make life as comfortable for her as possible, he engaged the services of a nurse to attend her during the day while he was at work. He was stricken when she died in 1964, sold the family home in Malvern and moved to his dream home on a treed acre, beside the Yarra at Templestowe, calling it his own National Park. Over the next ten years he gradually regained the momentum lost during his mother’s decline, his dedication to riding taking yet more of his time. It became difficult for even his best mates to see him. The bike ‘stats’ kept expanding until the possibility of grabbing the prized record became a probability. When he retired in 1975, he devoted the extra time in an all-out attack, but at fifty-seven, the going was getting harder. He had been knocked off his bike numerous times, his ribs had been broken, as had his neck. The writer’s wife helped rehabilitate Roy in our home more than once after a spell in hospital. He soldiered on for another nine years, becoming a ‘metric millionaire’ cyclist in 1981, then in March 1985, was diagnosed with the cancer that ended his extraordinary career. He was a decent, straight, human being who had lived a clean life, never had a bad word for anyone, was a conscientious scientist, neither smoke nor drank, was a rock, yet was served the death sentence of lung cancer. The tragic irony of it all was not lost on him nor his mates. Roy’s determination to beat Tommy Chambers was on track and came very close to being realised. He had created an Australian record but ultimately his miss was more than a mile.

End of a Chapter

The last few months of his life were particularly sad as blow after blow began hammering him down. It became clear to him that all the things he had worked for were turning to ashes. He felt frustration, helplessness and a consuming anger. The first shock was the discovery that his prized slides had been destroyed by mould; useless. He had no heart to look at them, even for their memories. For years, Roy hosted an annual YHA barbecue and get-together at his home. An ambition developed to bequeath his entire property, his home and book collection to the newer generation of YHA members, to offer it as a hostel where youthful travellers could be put up cheaply and perhaps learn to share his love of the environment. That hope was shattered when the Association’s administrators told him they would rather welcome his altruistic gift converted into cash; the man’s bitterness was understandable. Well into his illness but still mobile, Roy tried to recapture the happiness of the days spent at Mount Buffalo. Driving to the Chalet, he was so disillusioned with the changes there, he stayed only one night. That was his last outing. Peter Ralph was a lifelong friend in cycling, railways, photography and bushwalking who stuck with him to the end, attending his every want like a brother; his Horatio. In his last few days, Roy asked Peter to bring his bike to the hospital, and he was moved into a room where he could see it on the hospital verandah. Roy never knew it, but to us, his friends, the bitterest pill was delivered by the executor of his estate. Roy’s book collection was broken up and auctioned off, but before anyone could examine the all-important, leather-bound log with the meticulous records of his rides, the incredible statistics of his lifetime achievements, it was bundled up with other papers and taken to the tip.

Source:

Research undertaken by Graeme Wheeler.

(Image courtesy of Graeme Wheeler)

Reminiscences of My Close Friendship with Roy Busby

By Peter JO Ralph

I was a close friend of Roy Ernest Busby for over 36 years and during this period shared with him many of my hobbies and interests, the principle ones being cycling, bushwalking, photography, railways and mapping. I first met Roy in 1949, at an impressionable fifteen years of age during a Youth Hostels Association club night held at 161 Flinders Lane, Melbourne. I had just purchased an English Humber bicycle with 4-speed gears. I was also a member of the Cycle Touring Club of Victoria with former mate, the late Doug McLean. With no car in my family, I was very keen to further my horizons by joining the YHA cycling section and was advised to make contact with an Ad Verschure, but by a stroke of good fortune, was introduced to Roy instead. Thus commenced a long term bonding to a mate with similar interests. I guess it all started with Roy inviting me to his family home in Ardrie Road, East Malvern where he lived with his mother…a charming old lady! I was first shown his bike riding stats where all his daily mileages were recorded. These included his daily ride to work at CSL at Royal Park, where he was employed as a bio chemist. I was studying a chemistry course at Caulfield Tech at the time and found his assistance with the theoretical aspects of the course invaluable to me. Roy proudly showed me all the various places he had ridden around the nearby hills on daily rides, and showed me a wall map of Victoria, where he had shaded in the extremities of these rides and said that it was his prime objective to fill in the missing gaps to become a boundary rider. These solo day rides – some totalling in excess of 200 miles – took him to places as far away as Alexandra, Echuca, Cressy, Lorne, Tanjil Bren, Tidal River. His longest day ride was 327 miles in 24 hours. Roy then produced his extensive collection of maps and showed me the value in collecting one-inch-to-mile military maps for purposes of planning visits to various destinations. He then got out his photography album to show me pictures he had taken of peaks and waterfalls, all within a days ride from his home in East Malvern. I very soon realised we shared a passion for reaching such popular destinations as the Stevenson Falls, Masons Falls, Wombelano Falls and the peaks of Mt Beenak, Mt Dandenong, Mt Donna Buang, Mt Juliet, Mt Riddell and Mt St Leonard. In due course, I too found most were achievable within a days ride of Melbourne due to Roy’s encouragement and accompaniment on at least part of the way. What would normally occur on a typical day ride, I would meet Roy at say 4:00am on a Sunday at my parent’s home in East Malvern and we would ride together to Healesville where we would stop for a rest at Maroondah Dam lookout. To increase his stamina for the long climb to the top of the Black Spur, Roy would leave me there and ride solo on to Cathedral Range, to either do some mapping, or on to Alexandra to complete a boundary ride. This distance being beyond my physical capability, I was quite content to return home via the Acheron Way and Warburton. As a result of these rides with Roy, I improved my level of fitness and built up my confidence so extended rides ensured. These were over holiday long weekends to places such as Rubicon Falls, Woods Point, Walhalla, and Jamieson where Roy and I would carry tents and sleeping bags to camp overnight. Over the years, the extended rides ensured with other mates, which took us over the Alpine Road to Mt Hotham, the Grand Ride Road to Bulga Park, the Great Ocean Road to Lorne, Apollo Bay and Wilson’s Promontory. Some of these rides involved catching a train part of the way and most were combined with bushwalking. It soon became apparent from Roy that to really see the bush, one had to get off the beaten track. I was, therefore, encouraged by Roy to join the YHA bushwalking section and he accompanied me on several of their bushwalks. My first, being in July 1950 was a weekend walk from Powelltown, Big River were we camped overnight, then up the High Lead (where Roy boasted he could climb the 1,200 feet in 25 minutes), Downey’s Spur to Starling’s Gap and back to Warburton. The most popular destination for Roy and his mates was Mt Buffalo where we visited on several occasions to participate in climbing the Cathedral and watch Roy knock it off. Roy also decided to produce his own map of the Plateau and would drive to Buffalo with his bike mounted on the pack rack utilising the bike purely for measuring the various tracks. Most of the trips were with organised YHA parties or privately during public holiday weekends. These extended trips continued for well over ten years. Another extended walking trip was in the Cradle Mountain/Lake St Clair reserve area in Tasmania. This was encouraged by Roy over Christmas holidays in 1952. Roy being a member of the Melbourne Walking Club, I was unable to accompany him being a non-member. However, I was invited by a YHA mate to do an identical walk with the Catholic Walking Club, both clubs were going through the Reserve at the same time, so Roy and I constantly met up with each other at the various huts overnight and at Du Cane hut where we indeed were fortunate enough in meeting up with a Graeme Wheeler who became a close mate of Roy and myself over the years. During this visit, Roy and I came together again on a walk to Frenchman’s Gap, where Roy had retraced his steps two miles to correct a spelling error he had made in the visitors book at Lake Tahune – he had spelt the word “unforgettable’ with one ‘t’. Such was the nature of the man! Back in Hobart at the Hobart Walking Club meeting, Roy spoke about his walk through the Reserve, describing the climb of Mt Pelion West as like walking through ‘ready mixed concrete’ which brought a few laughs! Another hobby shared with Roy was knocking off various railway lines around the State where my being a railway enthusiast may possibly have influenced Roy with this interest. At every opportunity, Roy generally did not need much persuasion to accompany myself and a group of fellow railway enthusiasts on a pre-arranged excursion. The day trips were mostly hauled by steam trains to destinations such as Beech Forest/Weeaproinah, Timboon, Mortlake, Port Fairy, Mornington, Foster, Healesville and Warburton. Extended weekend railway excursions ensured to places such as Cudgewa, Orbost, Mt Gambier and Yarpeet with overnight sleeping carriages attached. Most of the excursions were to destinations that could only be reached on a goods train. Passenger trains had long been discontinued and most of these lines are now closed and pulled up, hence the fascination to reach them whilst we could. Photography was also a fascination for Roy. He always carried his camera on walking club trips, recording on black and white film in precise detail the places he visited and views from various peaks he had climbed. Some of Roy’s pictures appeared in the Melbourne Walking Club magazine ‘The Walker’. This was until I introduced him to Kodachrome in the early fifties when Roy decided to purchase a 35mm Exacta camera and commenced taking slides. Roy was an excellent photographer and was fascinated with photographing steam trains. As a testament to his high standard of photography, several of his pictures finished up in various train hobby publications. Peak bagging and waterfalls became a preoccupation for Roy. It also enticed me to climb peaks I would not normally have considered doing such as Mt Ellery and Mt Tingeringy in East Gippsland, and Mt Wilson at Wilson’s Promontory. As far as waterfalls were concerned, the more remote they were, the greater the challenge and I along with other mates, were indeed fortunate to have made our way into the Yarra Falls, long after the original tourist track from McVeights to Wallhalla was closed due to the 1939 bushfire. Another waterfall that I had the pleasure of reaching with Roy was the Matthina Falls at Healesville in the MMBW (Melbourne Water) Maroondah Dam catchment area and before the building of the dam. On another occasion, whilst I was living in Warrnambool, I was shown on a 1933 tourist map of the Western Coastal District the Aire Falls. No track was shown leading to the fall from the Hordon Vale/Apollo Bay Road. This immediately became a challenge for both Roy and myself and it took two attempts of bashing through lush rain forest along the Aire river valley to reach. These discoveries were as rewarding as climbing some of the more remote peaks. On extended walks led by Roy, we would always get a very raucous wake-up call at six o’clock to rise and shine. I distinctly remember trying to solicit Roy’s infamous wake-up call on a walk I was leading up to Mt Feathertop. At the Feathertop Hut where we camped the first night, it was my objective to get the entire party up to the summit next morning for the sunrise. However some couples were not impressed with being disturbed at such an early hour, so I asked Roy to be selective on who he woke. The next thing I noticed was Roy had packed up his tent, sleeping bag and was heading off! I will never forget the image silhouetted on the ridge against a big full moon heading for the summit alone – he simply had jacked up! During the early 1970s at the time of my divorce, I was placed in a single parent situation and found in Roy a very compassionate and caring man offering guidance and moral support in handling my affairs. One a month, we would meet at his Dallas Avenue, Templestowe home and have a meal at the local pub. Roy had moved to this lovely property after the death of his mother, and was very proud of his clinker brick home named Yarra View. It had a lovely wattle lined curved driveway with a backyard that gently sloped down to the bank of the Yarra River, a perfect spot for a field naturalist. He boasted that he had 120 gum trees in his backyard and was also proud of the fact that he had meticulously removed all the weeds in his back lawn by using a Stanley knife and scissors and carefully placing them in Wheetbix boxes for removal in the garbage collection. Once a year, Roy would invite all his friends from YHA over for a BBQ, to reminisce about all the fun times we had shared over the years. This all came to an abrupt end when Roy sadly passed away in 1985. Long may Roy be remembered.

Source:

Reminiscences of Peter Ralph.