Adventurer

Location: CofE*Q*61

“Gone” by Adam Lindsay Gordon (q.v.)

In Collins Street standeth a statue tall –

A statue tall on a pillar of stone.

Telling its story, to great and small,

Of the dust reclaimed from the sand waste lone.

Weary and wasted, and worn and wan,

Feeble and faint, and languid and low,

He lay on the desert a dying man,

Who has gone, my friend where we all must go.

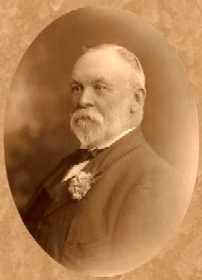

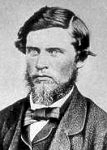

William Brahe, who was born at Paderborn, Germany on 16 January 1835, the son of (Wilhelm) Auguste Brahe (d 1887), civil servant and Maria (Mary) née Berendes earned much notoriety and criticism for his role as a member of the ill-fated Victorian Exploring Expedition (1860-61), headed by Robert O’Hara Burke (Melbourne General Cemetery) (“a death or glory man”). Arriving in Victoria in 1852, Brahe soon found work on the goldfields as a digger, carrier and stockkeeper where he earned much praise for his skill in driving wagons in adverse conditions.

In July 1860, having just a fortnight before driven a mob of cattle down from Queensland, Brahe was selected as a working man on the Expedition. The selection process was a charade; unknown individuals without the right connections had no chance of being appointed. Burke (“no experience as a surveyor or bushman…ignorant of navigation”) owed his appointment to the influence of ‘railway king’ John Vans Agnew Bruce (Melbourne General Cemetery) (“so accustomed to getting his way in colonial affairs that he would not even deign to…stand for the Legislative Assembly”) but was acknowledged by many, notably John Sadleir (q.v.) as being unsuited as leader having “no knowledge whatever of the resources by which an experienced bushman might find a living in an Australian desert” and “was continually losing his way in his short trips about Beechworth”; Brahe would later declare that Burke “could not safely be trusted 300 yards away from camp” and had to be accompanied during observation journeys. Brahe himself owed his appointment to the friendship between his elder brother William (Wilhelm) Alexander (1825-1917) and the German scientist Georg Neumayer (1826-1909) who was an influential member of the Royal Society and the Victorian Expedition Committee. But the fact remains, candidates with more experience were overlooked; only two of the original party of six Irishmen, five Englishmen, four ‘Indians’, three Germans and one American were skilled bushman much less men who had travelled beyond the settled districts.

When the disorganised party of 26 camels, 23 horses and six wagons finally left Royal Park on Monday 20 August 1860 at 4pm amid an estimated crowd of 10,000 to 15,000 well wishers (“the explorers started in carnival style”), never before had an expedition been move lavishly equipped, much of it new-fangled and absurd. In early September, the party stopped at Tragowell, near Kerang, Victoria, the home of the Holloways (q.v.), who offered the party “a long, improvised prayer” before heading towards Swan Hill. By the end of September, the first signs of division appeared at Gambala (“rent by feuding unprecedented in Australian exploration”). Matters came to a head on 12 October when George James Landells, second-in-command after Burke and camel-master resigned near Menindie, New South Wales; William John Wills (Melbourne General Cemetery) (“a light, clean, agile frame…and a handiness such as is often seen in a young girl”) became Burke’s resolute lieutenant. Through all of this, Brahe stood firm and focussed on the job at hand. Soon after arriving at Menindie, Burke divided the party (“one of the most significant decisions of the expedition…his greatest crime”) taking Wills, Brahe, King, Gray, McDonough, Patten, Dost Mahomet and between five and six months of supplies leaving the rest in command of William Wright, manager of Kinchega a sheep and cattle station on the Darling; fatally, Wright’s group was left without a surveyor to enable the party to meet at Cooper’s Creek and also lacked additional animals and men to bring up the remaining supplies. The forward party of Burke reached Cooper’s Creek on 11 November from Menindie after just 23 days (“an exceptionally quick time”). But Burke’s impetuosity and “eagerness to set off knew no bounds” and he left Camp LXV on 16 December on a rush to reach the Gulf of Carpentaria taking Wills, Gray and King as well as just twelve weeks provisions using six camels and a horse to carry the supplies, instead marching the 1500 miles on foot with only a single rest day – 24 December.

Eager to join Burke, Brahe had to remain at the depot and was given command of the three men; as he and Wills were the only two able to use a compass, it was natural for Brahe to stay. Appointed an officer, Burke’s oral instructions to Brahe, were to remain for “three months and longer if he could”; more cautiously, Wills asked him to remain four months. With the help of the remaining men, Brahe went about building a stockade of branches and saplings about three feet high to protect the men and provisions from attack by the local Aborigines. Apart from the odd duck and fish to supplement their diet, the men survived on “a pint of boiled rice with some sugar for breakfast, some damper and a little salt pork or beef for lunch, and two biscuits and a pint of tea at night”. By mid-April 1861, Brahe’s situation was becoming increasingly desperate. Burke had not yet returned, Wright had still not arrived, Patten was suffering from scurvy, and if Brahe was to make it back to Menindie with enough provisions he would have to leave soon. And so on the morning of 21 April, they set off, but not before Brahe left a camel trunk containing a note in a bottle (“the depot party of the VEE leaves this camp today to return to the Darling”) and a month of provisions; it was Brahe who carved on the tree “DIG UNDER”. By a luckless coincidence, Burke, Wills and King, starving, exhausted and dishevelled stumbled back to the depot later that day to find it deserted having just a few days before spent a whole day burying Gray; nor did it help that Wills, so often overlooked for criticism by historians, contributed to the fiasco due to his errors in charting their course, leading the party to take a longer route. By the end of June, Burke and Wills were dead from starvation and exhaustion. On his return to the Darling, Brahe by chance came upon Wright and his party heading north near Bulloo on 29 April a meeting that did much to raise the morale of the two groups; Wright’s party was hardly in better condition than Brahe’s men. Both Wright and Brahe decided to head back to Cooper’s Creek, arriving on 8 May, but found nothing to indicate Burke had returned and soon departed for the final time; it was yet another in a succession of agonising mischances that marred the Expedition where little stood between success and failure.

Flawed from the start, yet successful in achieving the first to cross the continent (though Burke and Wills were but 20 kilometres from the coast), it nevertheless cost £57,840 and the lives of seven men. Having rushed to reach Bendigo, Brahe relayed word to the Expedition Committee on the evening of 29 June; he later joined Alfred William Howitt (Bairnsdale Cemetery) on his search for Burke. Returning to Bendigo on 2 November he telegraphed the “thrilling news” to Melbourne that Burke, Wills and Gray were dead, but King had been found alive by Howitt. At Castlemaine, a crowd surrounded Brahe and asked him “fifty questions in a breadth” forcing him to retreat to the Castlemaine Hotel where he explained to a breathless audience what had happened. But on his return to Melbourne, Brahe soon fell victim to a sustained campaign of criticism against his conduct. Writing to The Argus on 12 November 1861, he asked the editor to “abstain from continuing to publish one-sided and garbled commentaries” arguing that “every supposed criminal is accorded a suspense of judgement until he is fairly tried and found guilty” and pleading “a right to claim the same indulgence”. In a long and detailed letter to the Expedition Committee, Brahe went some way to explain his actions and repair his damaged reputation against the two most serious charges that he had left the depot earlier than instructed; and that on returning to the depot with Wright, he had failed to notice Burke’s return. Pilloried by the Royal Commission for “retiring from his position at the depot” who found his decision “deserving of considerable censure”,

Brahe spent some years in far north Queensland as a pastoralist and later in New Zealand and Fiji where in 1874, he married Elise née Hinge (Hinze) (d 1927); they had at least seven children: Frederic Charles (1878-1919) who married the composer Mary (May) Hannah née Dickson (1884-1956), Pauline Theresa (b 1879) married John Parslow 1902, Hans William (b 1881), Frieda Marie (b 1883) married Arthur Percival 1911, Elsa (1885-1975), Alexander (b 1887) possibly married Alice Taylor 1910, Hilda Wilhemina (1888-1968), and Arthur Augustus (circa 1886-1966).

Residing at Enmore – St. Kilda Street, Elwood, Brahe died on 16 September 1912 aged 77 years; he is depicted in William Strutt’s painting “The Burial of Burke” (1911) standing at right holding a hat and spade.

With the pistol clenched in his failing hand,

With the death mist spread o’er his fading eyes,

He saw the sun go down on the sand,

And he slept, and never saw it rise;

‘Twas well; he toil’d till his task was done,

Constant and calm in his latest throe,

The storm was weathered, the battle won,

When he went, my friends, where we all must go.

Source:

The Age 22 August & 2 September 1904.

The Argus 12 & 14 November 1861.

Bonyhady, T., “Burke & Wills. From Melbourne to Myth” (1991).

Murgatroyd, S., “The Dig Tree. The Story of Burke and Wills” (2002).

Beckler, H., “A Journey to Cooper’s Creek” (1993).

De Serville, P., “Pounds and Pedigrees. The Upper Class in Victoria 1850-80” (1991).

ADB Volume 3 1851-90 (A-C).

(Image reproduced by kind permission of the Georg von Neumayer Polararchiv, Pfalzmuseum fuer Naturkunde (POLLICHIA Museum), Bad Duerkheim)